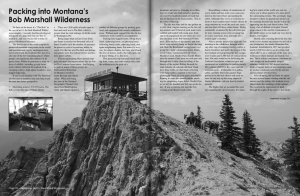

Packing into Montana’s Bob Marshall Wilderness

As published in West Coast Horsemen, Sept. 2015

To those in the know it’s “The Bob” to the rest of us it’s the Bob Marshall Wilderness complex. I recently had the privilege of being part of a nine-day trip into this remarkable, and very bucket list worthy, region of Northwest Montana.

The Bob is one of the most completely preserved mountain ecosystems in the world and has remained largely unchanged since Lewis and Clark first explored the area. It is also one of the few remaining places where people can experience the outdoors in its purest form. Within its perimeter a wide variety of wildlife, including grizzly bears, roam without intrusion throughout deep sweeping valleys, high alpine meadows, and rugged ridge tops.

The Bob is one of the most completely preserved mountain ecosystems in the world and has remained largely unchanged since Lewis and Clark first explored the area. It is also one of the few remaining places where people can experience the outdoors in its purest form. Within its perimeter a wide variety of wildlife, including grizzly bears, roam without intrusion throughout deep sweeping valleys, high alpine meadows, and rugged ridge tops.

If you’re not familiar with The Bob here are two sets of numbers that may help to put the area into better perspective.

- Stretching across 1,535,352 acres, The Bob is twice the size of Rhode Island.

- There are 1,856 miles of trails open to foot and stock use in The Bob, which is greater than the total mileage of all the roads in Washington DC.

Being larger than an East Coast State and home to nearly two thousand miles of horse friendly trails the number of spectacular places to visit is beyond my ability to count. For this run into The Bob our destination points were fire lookout towers and historic patrol cabins.

Being larger than an East Coast State and home to nearly two thousand miles of horse friendly trails the number of spectacular places to visit is beyond my ability to count. For this run into The Bob our destination points were fire lookout towers and historic patrol cabins.

Vital in maintaining these historic support structures are organizations like the Forest Fire Lookout Association. And helping to pack in many of these groups are Backcountry Horsemen of Montana members Andy Breland and Chuck Allen. When not being the stars of the National Geographic Channel’s hit show Dead End Express, Andy and Chuck support a number of different groups by packing gear, food, and equipment into remote wilderness areas. Without pack support like this far less wilderness work would be accomplished.

Packing four legged beasts, lifting heavy loads, tightening knots, retightening knots, following lonely trails, adjusting loads, and again retightening knots. For some it’s a career, for others a hobby, for Andy and Chuck the love of horses, mules, the trails and a lot of heavy lifting, it’s a life style.

This particular trip had pack stock hauling food, water, and tools twenty miles into the wilderness to the peak of a mountain and prior to returning to civilization we would also find ourselves packing out over five hundred pounds of trash that had no business in the backcountry. This is the story of that trip.

This particular trip had pack stock hauling food, water, and tools twenty miles into the wilderness to the peak of a mountain and prior to returning to civilization we would also find ourselves packing out over five hundred pounds of trash that had no business in the backcountry. This is the story of that trip.

The sky was blue and the sun golden on a cold, clear, August morning as the five riding animals and 10 head of pack stock were saddled and loaded with camp gear, food, and work equipment for our multi-day visit into the heart of the Bob Marshall Wilderness.  After the last of the manti’s and bear boxes were securely hung we began the long ride from the Benchmark campground west to our first night’s destination point, Basin Creek Cabin. Continental Divide Trail, Hoadley Creek, Stadler Pass, Scarlet Mountain; the names of the areas we rode past and through don’t come close to telling of the beauty of the region. Riding through the stark remains of a decade old burn. Dead trees bone white, or char black, towering over steep valleys carpeted in fireweed glowing in sheets of vivid pinks and purples. Pausing to water the animals before attacking the steepening slopes below Stadler Pass as we left the deadfall and felt our spirits rising. It was a glorious ride into the first evening at the Basin Creek Cabin.

After the last of the manti’s and bear boxes were securely hung we began the long ride from the Benchmark campground west to our first night’s destination point, Basin Creek Cabin. Continental Divide Trail, Hoadley Creek, Stadler Pass, Scarlet Mountain; the names of the areas we rode past and through don’t come close to telling of the beauty of the region. Riding through the stark remains of a decade old burn. Dead trees bone white, or char black, towering over steep valleys carpeted in fireweed glowing in sheets of vivid pinks and purples. Pausing to water the animals before attacking the steepening slopes below Stadler Pass as we left the deadfall and felt our spirits rising. It was a glorious ride into the first evening at the Basin Creek Cabin.

Resembling a colony of mushrooms of every shade and hue, tents were soon scattered on the forest floor surrounding the cabin. Although they serve as welcome retreats in foul weather most visitors choose to sleep outdoors to avoid the pack rats, mice and bats that

Resembling a colony of mushrooms of every shade and hue, tents were soon scattered on the forest floor surrounding the cabin. Although they serve as welcome retreats in foul weather most visitors choose to sleep outdoors to avoid the pack rats, mice and bats that

call these cabins home. Being continually awakened by the soft pitter-patter mice running across your sleeping bag, or worse your head, does not make for a restful night’s slumber.

After a mostly mouse free night the first morning in the wilderness brought with it cup after cup of steaming cowboy coffee, a hearty breakfast and much discussion of the best method of transporting the day’s cargo over 6 miles and 3,400 feet of vertical elevation. Not only would we be delivering the Lookout Association volunteers gear and equipment we would also be packing nearly fifty gallons of H2O to the water starved mountain peak. Collapsible five-gallon cubes carefully fitted into pannier bags proved to be the best choice and soon we were on our way up the steep slopes of Jumbo Mountain with our heavily loaded animals.

After a mostly mouse free night the first morning in the wilderness brought with it cup after cup of steaming cowboy coffee, a hearty breakfast and much discussion of the best method of transporting the day’s cargo over 6 miles and 3,400 feet of vertical elevation. Not only would we be delivering the Lookout Association volunteers gear and equipment we would also be packing nearly fifty gallons of H2O to the water starved mountain peak. Collapsible five-gallon cubes carefully fitted into pannier bags proved to be the best choice and soon we were on our way up the steep slopes of Jumbo Mountain with our heavily loaded animals.

The higher that we ascended the more awe inspiring the views became. It’s amazing how much of the world you can see when you’re three quarters of a mile above the surrounding terrain. The seemingly large meadows where we grazed our animals in the morning became tiny specks before disappearing into the vast forest below. Not being a fan of altitude or heights I found great solace in the careful examination of the uphill slopes as we made our way slowly higher, ever higher.

Shortly after crossing above the tree line with its few stunted specimens we arrived at our destination, the Jumbo Mountain Fire Lookout. Established in 1937 and perched nearly 8,300 feet above sea level this, and others like it, are a vital part of the story of a wilderness where humans are merely visitors. These solitary and remote structures invoke images of backcountry rangers standing watch over 360 degrees and hundreds of square miles of awe-inspiring country as they constantly scan for the tell tale smoke plumes of forest fires.

Shortly after crossing above the tree line with its few stunted specimens we arrived at our destination, the Jumbo Mountain Fire Lookout. Established in 1937 and perched nearly 8,300 feet above sea level this, and others like it, are a vital part of the story of a wilderness where humans are merely visitors. These solitary and remote structures invoke images of backcountry rangers standing watch over 360 degrees and hundreds of square miles of awe-inspiring country as they constantly scan for the tell tale smoke plumes of forest fires.

After dropping off our loads we spent the next several hours visiting with the volunteers and the solitary fire lookout as we talked about the workings of the lookout.  We even had the opportunity to peak through the sights of the tower’s fire finder.

We even had the opportunity to peak through the sights of the tower’s fire finder.

The Osborne Fire Finder is a type of alidade that is used to determine the directional bearing of a smoke plume in order to provide fire crews with forest fire information. It’s fascinating.

The arrival of dark clouds on the horizon signaled that it was time to head down to the safety of the valley far below. A mountain top fire tower is not a place where I would want sit out a storm so we bid our friends a fond adieu and started down, our pack animals much lighter than when we arrived.

After a pleasant and uneventful journey down to the foot of Jumbo Mountain I was jolted back into awareness by the swift swivel of my mount’s ears. Crossing the trail only 30 feet ahead of us was a bear and to my mind a large bear at that, although the ears seemed smallish and the hump on his shoulders seemed odd. None of our riding or pack stock seemed too concerned by the bear’s appearance and so we continued to observe as Mr. Usus followed us alongside the trail for a number of minutes.

After a pleasant and uneventful journey down to the foot of Jumbo Mountain I was jolted back into awareness by the swift swivel of my mount’s ears. Crossing the trail only 30 feet ahead of us was a bear and to my mind a large bear at that, although the ears seemed smallish and the hump on his shoulders seemed odd. None of our riding or pack stock seemed too concerned by the bear’s appearance and so we continued to observe as Mr. Usus followed us alongside the trail for a number of minutes.

The rodeo began suddenly and without warning. A sickening lurch followed by a quick dip accompanied by a sudden leap to the side. I managed to stay mounted and once the ruckus slowed I saw what caused the commotion. Wading shoes left on the bank of the river by a group of hikers. A grizzly bear produced nothing but a deep yawn. A few tennis shoes, however, is cause for wide-eyed terror. Go figure.

The rodeo began suddenly and without warning. A sickening lurch followed by a quick dip accompanied by a sudden leap to the side. I managed to stay mounted and once the ruckus slowed I saw what caused the commotion. Wading shoes left on the bank of the river by a group of hikers. A grizzly bear produced nothing but a deep yawn. A few tennis shoes, however, is cause for wide-eyed terror. Go figure.

Please join us next month when I’ll recount packing over 500 pounds of barbed wire and other assorted trash out of the Bob and our encounter with another trail terror, a ___________.