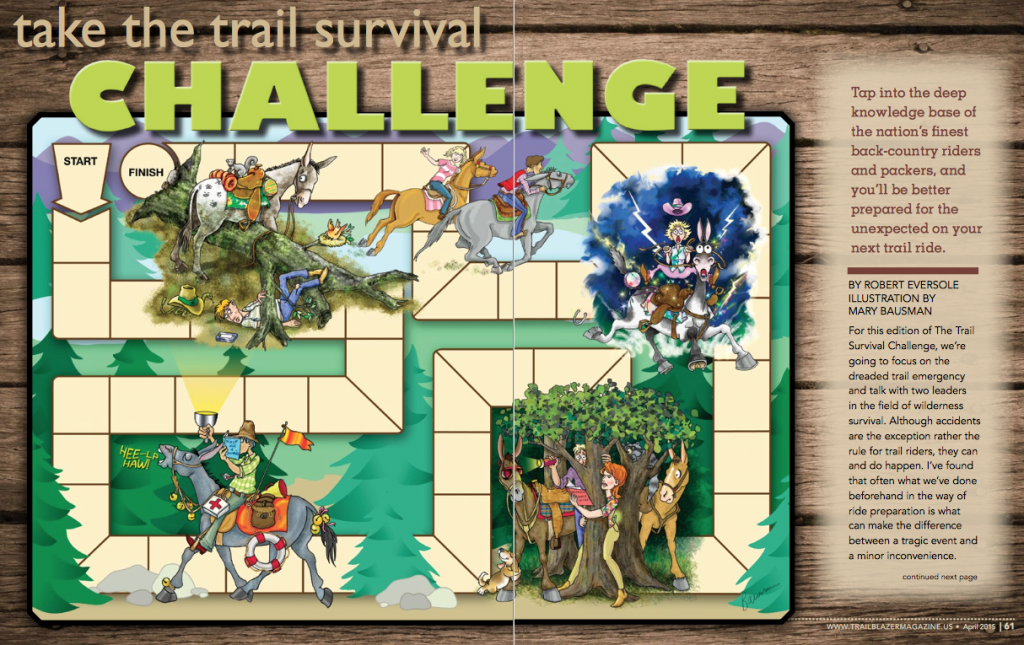

For this edition of Trail Survival Challenge we’re going to focus on the dreaded trail emergency and talk with two leaders in the field of wilderness survival. Although accidents are the exception rather the rule for trail riding they can and do happen. I’ve found that often what we’ve done beforehand in the way of ride preparation is what can make the difference between a tragic event and a minor inconvenience.

For this edition of Trail Survival Challenge we’re going to focus on the dreaded trail emergency and talk with two leaders in the field of wilderness survival. Although accidents are the exception rather the rule for trail riding they can and do happen. I’ve found that often what we’ve done beforehand in the way of ride preparation is what can make the difference between a tragic event and a minor inconvenience.

John Hays teaches military personnel the art of wilderness survival and has done so for over 30 years. Barb Taylor is a survivor of a horrible trail riding accident and a noted natural hoof care practitioner. Together they teach riders in the Pacific Northwest how to best respond and react to the situations that trail riding can throw at us by providing information, knowledge, and tools to aid in Managing Unplanned Life Emergency Situations. You can learn more about what to do when “just a day ride” turns into something more at their website www.justadayride.com.

As you may have guessed from the M.U.L.E.S acronym Barb and John are big fans of the equine variety known as a mule. As such this month I’ve inserted mule in place of horse throughout the text. Rest assured what you’ll learn will work for horses too!

Without further ado let’s jump into some of the questions that Trail Blazer readers have sent in.

#1 – Summer thunderstorms scare me. What should I do if a thunderstorm pops up during a ride? – Sincerely, Ella Trician

#1 – Summer thunderstorms scare me. What should I do if a thunderstorm pops up during a ride? – Sincerely, Ella Trician

- Rides over; load up and head home.

- Metal horseshoes attract lighting. Get away from your horse ASAP.

- Find a relatively safe area.

- Hide in a grove of trees and wait out the storm.

To stand against the deep dread-bolted thunder? In the most terrible and nimble stroke, Of quick, cross lightning? (Wm. Shakespeare, “King Lear”)

Having been in the high country during more than a few storms I can tell you that lightning and the associated thunderclaps scare me too! Despite listening to the forecast, weather tends to happen and it’s how we deal with it that will decide how memorable the ride is. On average over 50 lightning fatalities occur each year. I have no intentional of being a statistic and although the National Weather Service says no place outside is safe when thunderstorms are in the area – there are things that you can do to reduce the risk. Let’s see what John and Barb have to say about thunderstorms.

If a pop up storm means that the ride is over we may not spend much time in the saddle this summer. If we do what we can to reduce the risk to an acceptable level we can stay on the trail much longer.

A common belief that has never been proven is that metal horseshoes will attract lightning. That being said, dismounting will get you lower to the ground and decrease your likelihood of being struck.

Choice C is wonderful, but first we have to decide what a relatively safe area is. To lessen the chances of a lightning tragedy follow these recommendations from the National Weather Service.

- Avoid open fields, the top of a hill or a ridge top.

- Stay away from tall, isolated trees or other tall objects. If you are in a forest, stay near a lower stand of trees.

- If you are in a group, spread out to avoid the current traveling between group members.

- If you are camping in an open area, set up camp in a valley, ravine or other low area. Remember, a tent offers NO protection from lightning.

- Stay away from water, wet items, such as ropes, and metal objects, such as fences and poles. Water and metal do not attract lightning, but they are excellent conductors of electricity. The current from a lightning flash will easily travel for long distances.

While option D is a much better choice than staying on an exposed ridge during a storm, you should remember to stay away from the tallest tree in the grove and to tie your mule to a low bush not to a tall tree that could channel electricity.

#2 – The park where I ride doesn’t have cell phone service. What are my options in case of an emergency? – Yours, Bar Less

#2 – The park where I ride doesn’t have cell phone service. What are my options in case of an emergency? – Yours, Bar Less

- 911 works whether or not you have signal bars. Don’t worry about it.

- Always ride with a buddy.

- Be current with your 1st Aid and CPR qualifications.

- There are many types of emergency communications devices available. Research and learn which works best for you.

B., C., and D. are all correct answers for my money. Many trail riders whether deep in the backcountry, or a front country day ride, are without the safety net of cell service. I know Barb and John have more to weigh in on the subject so without further ado.

Selection A. is false and will get you hurt. While it is true that in marginal situations a text message may have better luck in being transmitted, areas with no signal have just that, no signal to send any message.

- is for Buddy. Most kids aren’t allowed to play away from home by themselves and neither are we. There is safety in numbers. In the case of an accident two people will be more able to deal with the situation than a single hurt rider by himself.

- is for CPR. Every trail rider should know 1st Aid and CPR techniques. It could save someone’s life, or your own. Having a 1st Aid kit isn’t enough; you must also have the knowledge to use the tool.

Option D. covers a wide swath of tools that are available to us. From a whistle to brightly colored signal flags to personal locator beacons, there are many instruments available to summon help when it’s needed. Some are more effective than others. Part of the preparation that we do before a ride should include a review of how you’ll call for help in case of an accident. John and Barb carry a PLB with them on every ride, whether or not they’re in a remote area.

#3 – I hear a lot of horror stories about accidents that happened while trail riding. Is trail riding really worth it and what do I do in case my riding buddy gets hurt? – Truly, Bee Prepared

#3 – I hear a lot of horror stories about accidents that happened while trail riding. Is trail riding really worth it and what do I do in case my riding buddy gets hurt? – Truly, Bee Prepared

- Call 911 as soon as there’s a problem.

- Tell your buddy to cowboy up and ride on.

- Assess the situation and react accordingly.

- Leave them and ride on.

One of the trail ride gone wrong stories you may have heard happened to this month’s expert; Barb Taylor. Barb came off her mule during a mountain trail ride. In spite of a combination of errors that could easily have proven fatal, Barb had access to a PLB device. After laying on the side of a mountain for 24 hours with a broken femur a helicopter rescue crew flew her straight into an emergency surgical unit. You can read more about the accident and what changes it prompted at www.justadayride.com.

One of the trail ride gone wrong stories you may have heard happened to this month’s expert; Barb Taylor. Barb came off her mule during a mountain trail ride. In spite of a combination of errors that could easily have proven fatal, Barb had access to a PLB device. After laying on the side of a mountain for 24 hours with a broken femur a helicopter rescue crew flew her straight into an emergency surgical unit. You can read more about the accident and what changes it prompted at www.justadayride.com.

Bee, yes, trail riding is most definitely worth it. The mountain vistas framed between your mule’s ears, the steady clip clop of hooves moving down the trail, and any of a hundred more wonderful memories make trail riding a worthwhile experience. There are certainly risks that are entailed, but I, for one, am much more concerned about the drive to the trailhead than my amble down a forested path. John made a point of reminding us “bad news sells”. He’s right. The vast majority of uneventful rides are quickly forgotten when the rare accident occurs. Barb is a survivor of a trail riding disaster. You can read about her experience in the sidebar, but first let’s see what she and John have to say about what to do if an accident happens.

Call 911 immediately? This may not be an option. Bee hasn’t told us if cell reception is available where she rides or if she carries any type of emergency beacon. Having some way to call for help is important, and should always be on you, not your riding animal.

Cowboy up? What a terrible thing to say to anyone let alone someone who is hurting. If your riding partner reacts to accidents in this manner find a new one.

Preparation is key again and the ability to evaluate the situation is just one example of knowledge being crucial. 1st Aid courses from the basics to wilderness survival, are widely available, extremely worthwhile, and all too often not taken advantage of.

Unfortunately D. happens. In Barb’s case two members of the group left. Not to summon help, but to continue their ride. The cardinal rule that these irresponsible two violated is “The group that leaves together returns together.”

#4 – My husband is directionally challenged. This often results in our getting back to the trailer well after dark. What should we do when our flashlight runs out of batteries? -Sincerely, Ina Dark

#4 – My husband is directionally challenged. This often results in our getting back to the trailer well after dark. What should we do when our flashlight runs out of batteries? -Sincerely, Ina Dark

- Horses can see in the dark. Ride on!

- Hug a tree. Stay put till sunrise.

- Get a new husband.

- Bring extra batteries.

We’ve all been in Ina’s shoes at some point. It’s been a long day and we’re late getting back to camp and a hot meal. Do we forge ahead through uncertain terrain, or do we play it safe by spending a night on the trail to return at first light? Let’s see what the experts have to say!

Numerous research experiments have shown that equines have excellent night vision compared to ours. That doesn’t mean that continuing a ride after dark is the safe bet. Your mule will most likely see, and avoid, the low hanging branch. However, you may not be so lucky, and a face full of tree limb is a sure way to end a ride in the hospital. So much for choice A.

Option B. is the safest choice by far. Being well prepared opens the door to many options and prevents riders from having to choose the lesser of the evils.

Option C. Nope, we’re not even going to touch that one!

Option D. returns us to our discussion of being prepared, but also brought up the topic of just how fragile night vision is. You’ve noticed this phenomenon when you leave a brightly lit room and go into the dark. It takes a while for you to see clearly in the darkness. The same thing happens to your mule when you shine a light in its eyes. The superior night vision of your mule is suddenly gone. Worse an equine’s night vision takes longer to return to normal than ours, so be careful about where you shine that flashlight.

With that we’d better wrap up this edition of The Trail Survival Challenge. Do you have a trail riding question that you’ve been aching to learn more about? Have you wondered if you did the right thing in a certain trail situation? Send us your questions and we’ll see what the best horse experts in the world have to say.

With that we’d better wrap up this edition of The Trail Survival Challenge. Do you have a trail riding question that you’ve been aching to learn more about? Have you wondered if you did the right thing in a certain trail situation? Send us your questions and we’ll see what the best horse experts in the world have to say.